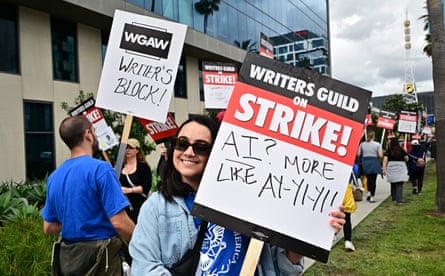

On the picket lines outside Los Angeles film studios, artificial intelligence has become a central antagonist of the Hollywood writers’ strike, with signs warning studio executives that writers will not let themselves be replaced by ChatGPT

That hasn’t stopped tech industry players from selling the promise of a future in which AI is an essential tool for every part of Hollywood production, from budgeting and concept art, to script development, to producing a first cut of a feature film with a single press of a button.

The writer’s strike has put the spotlight on escalating tensions over whether an AI-powered production process will be a dream or a nightmare for most Hollywood workers and for their audiences.

Los Angeles’s AI boosters tout the latest disruptive technology as a democratising force in film, one that will liberate creators by taking over dull and painstaking tasks like motion capture, allowing them to turn their ideas into finished works of art without a budget of millions or tens of millions of dollars. They envision a world in which every artist has a “holographic vision board”, which will enable them to instantly see any possible idea in action.

Critics say that studio executives simply want to replace unionized artists with compliant robots, a process that can only lead to increasingly mediocre, or even inhuman, art.

All these tensions were on display last week when tech companies that specialise in AI, including Dell, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise and Nvidia, were among the sponsors of an “AI on the Lot” conference in Hollywood, which attracted an estimated 400 people to overflowing sessions about how artificial intelligence was disrupting every facet of film production. One tech investor described the mood as both high energy and high anxiety.

The day before the AI conference, a crowdfunded plane had flown over multiple studios with a banner message: “Pay the writers, you AI-holes.” But several speakers at the AI LA conference argued that fear of artificial intelligence is for the weak.

“The people who hate it or are fearful of it are insecure about their own talent,” said Robert Legato, an Academy Award-winning visual effects expert who has worked on films like Titanic, the Jungle Book and the Lion King.

“It’s like a feeling amplifier,” said Pinar Seyhan Demirdag, an artist turned AI entrepreneur. “If you feel confident, you will excel. If you feel inferior –,” she paused. The tech crowd laughed.

‘No more Godfather, no more Wizard of Oz’

It’s hard to know how exactly the battles over AI in Hollywood will play out, given the heavy haze of marketing bombast, fearmongering and simple confusion about the technology that’s currently hovering over the industry.

“A lot of us are at a cocktail party pretending we know what we’re talking about,” Cynthia Littleton, the co-editor-in-chief of Variety magazine, told the Hollywood AI conference.

But it’s clear that some of the emerging conflicts will focus on job losses from automation, copyright and intellectual property disputes and deeper questions about how much a profit-driven studio system actually cares about human creativity.

Getty Images recently sued Stability AI, the maker of a prominent text-to-image generator, accusing it of improperly training its algorithms on 12m Getty photographs, while officially working with another AI company, Nvidia, to develop licensed photo and video AI products that will provide royalties to content creators

Because AI video technology is still lagging behind audio or image generation, the music industry is currently “the tip of the spear” for AI battles, said Littleton, pointing to the controversy over recent AI simulations of songs by Drake and The Weeknd. But Hollywood is gearing up for the era of AI-generated actors: Metaphysic, an AI company that specializes in “deep fakes”, announced a partnership that would work to develop new tools for the clients of Creative Artists Agency CAA’s, a major entertainment and sports talent agency.

Joanna Popper, the talent agency’s new “chief metaverse officer”, told Deadline in January that the new technology will offer flexibility to actors and other entertainers, who will still retain the rights to their image and likeness. “Some actors have done commercials where essentially their synthetic media double did the commercial rather than the actor traveling around the world,” she said.

“If the actor isn’t available for the reshoots a director needs, you can have a stand-in for the actor and then use this technology for face replacement and still get the job done in the needed timeline,” Popper offered. “If you wanted the actor to speak in a different language, you could use AI to create an international dub that sounds like the actor’s voice speaking various other languages.”

Some Hollywood writers and actors have begun to denounce these developments, arguing that the coming age of AI is a threat to workers across the industry. “AI has to be addressed now or never,” Justine Bateman, a writer and director who was a television actor in the 90s, argued in a viral Twitter thread, calling on the Screen Actors Guild to follow the writers’ guild in making AI regulations a central part of their coming contract negotiations. “If we don’t make strong rules now, they simply won’t notice if we strike in three years, because at that point they won’t need us.”

The more than 160,000 members of Sag-Aftra, which includes screen actors, broadcast journalists and a wide range of other performers and media professionals, are currently voting on whether to authorize their own strike.

Many Hollywood critics argue that too much reliance on AI in film-making is a threat to the very humanity of art itself. Speaking at Cannes, actor Sean Penn expressed support for writers, calling the use of AI in writing scripts a “human obscenity”. “ChatGPT doesn’t have childhood trauma,” one viral writers strike sign quipped.

If studios pivot to producing AI-generated stories to save money, they may end up alienating audiences and bankrupting themselves, leaving TikTok and YouTube as the only surviving entertainment giants, the Hunger Games screenwriter Billy Ray warned on a recent podcast.

“No more Godfather, no more Wizard of Oz, it’ll just be 15-second clips of human folly,” he said.

Black film and TV writers in particular have been speaking out about the ways AI could be used by studios to generate “diverse” content without actually having to work with a diversity of artists.

“We’re going to get the stories of people who have been disempowered told through the voice of the algorithm rather than people who have experienced it,” the Star Trek writer Diandra Pendleton-Thompson warned on the first day of the writers strike.

‘AI lacks courage to write something truly human’

Some recent entrants to the AI industry say that the current technology is being overhyped, and its likely impact, particularly on writers, has been exaggerated.

“When people tell me the studios are going to replace writers with AI, to me, that person has never tried to do anything really difficult with large language models,” said Mike Gioia, one of the executives of Pickaxe, a new Chat GPT-based platform for writers with a few hundred paying customers.

He called the idea that AI could produce full scripts “science fiction”.

“The worst-case scenario for writers is that the size of writers rooms is reduced,” he said.

Many early Pickaxe customers, Gioia said, are using it to automate mundane tasks, like filing internal reports or making interactive FAQs for e-commerce sites. While the technology can generate a rough draft of a formulaic TV script for a writer to tinker with, Gioia said, he believed it would be “a fool’s errand” to try to get it to produce good dialogue. While AI is good at understanding the “meta structure” of a piece of text, Gioia said, “It lacks the courage to try to write something truly human.”

AI writing tools could have big effects in less glamorous segments of the film industry. Pickaxe is currently exploring whether it can use the AI tools to help automate the budgeting process of reading a script, breaking down the different visual effects needed to produce each shot and then estimating the cost of those effects, Ian Eck, another Pickaxe executive, said.

Writers have made AI central to their strike in part because “it’s a good story”, Gioia argued and partly because they are much less accustomed to being disrupted by technology than other industry workers.

“A lot of people in post-production have lived through multiple technological revolutions in their fields, but writers haven’t lived through a single one,” he said.

James Blevins, whose decade-long career in special effects and post production has taken him from 1996’s Space Jam to The Mandalorian, told attendees of the AI conference in LA that the anxiety around AI reminded him of the anxiety around the digitization of film in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“I’ve always done the job that will be replaced. I’ve always been automated out of my job. It’s just the way it is,” he said.

He cautioned that there was no way to escape the changes that AI would bring to the industry.

“It’s so disruptive, it’s kind of like being afraid of the automobile, or, ‘Oh my God, we shouldn’t go to the moon,’” he said.

What went unanswered in the panel discussion was how many of Hollywood’s technical workers, from set designers to hairstylists, would be able to translate their skills into a more virtual film world – and how many might simply be laid off.

IATSCE, the union representing 168,000 entertainment industry technicians, artisans and craftspeople, announced in early May that it would be forming its own commission on artificial intelligence to investigate the impact of the technology on workers. The union is also interested in helping to unionizing new segments of workers that may emerge in the wake of AI disruptions – including the new category of AI wranglers that the tech boosters are currently calling “prompt engineers”, said Justin Loeb, IATSCE’s director of communications.

But in a tech industry driven by hype, it’s still not clear how much change is really coming, or how fast.

“VR was going to be huge in the 90s, and well, that didn’t really happen and then it was going to be huge about five years ago and that hasn’t happened,” Gregory Shiff, who works on media and entertainment issues for Dell, said on the panel briefly moderated by an avatar of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. “Is AI going to be the same? I don’t think so, but I don’t know.”